Thanks, thats very interesting  . Wonder why more manufacturers dont try and perfect the concept.

. Wonder why more manufacturers dont try and perfect the concept.

It's not for lack of development, it's like an antigravity car or a carburettor that enables a car to run on water. Some things simply are beyond the laws of physics.

I was tempted to start a long dissertation on balance dynamics but let me just give you the expurgated version (which is too long as is). Some engine layouts are forever doomed to be "rough-running" and the V-10 is one of them. The simplest example is the single cylinder engine. A piston going up and down within the cylinder is continually reversing direction and accelerating in the opposite. The piston moving within the cylinder tends to want to push the remainder of the engine in the opposite direction (Sir Isaac's Second Law). And just to complicate affairs, at top dead center and bottom dead center, just before it reverses direction, the piston has zero vertical velocity and its momentum is nil.

Because Force = Mass x Acceleration, both the amount of force

and the direction of that force vary dramatically every time the crank turns a full revolution. Unless countered, these imbalances cause the engine to vibrate.

Since I have artificially limited this example to a single cylinder engine, the only practical solution to null the vibration is a counterbalancer. This is nothing more than a mass (or weight) equal to that of the piston, usually mated to the crank itself by a gear that spins in the opposite direction and at the same rate as the crank. This results in two equal masses, each perpetually traveling in the opposite direction as the other and always at the identical velocity. This satisfies Sir Isaac and the primary imbalance is canceled.

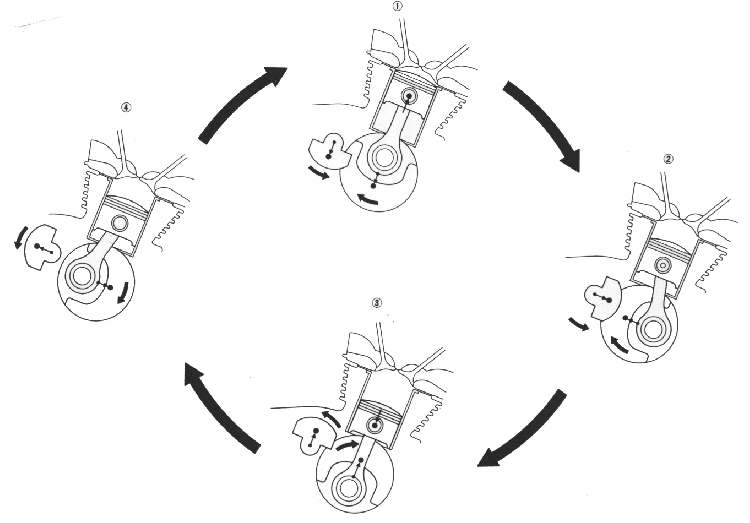

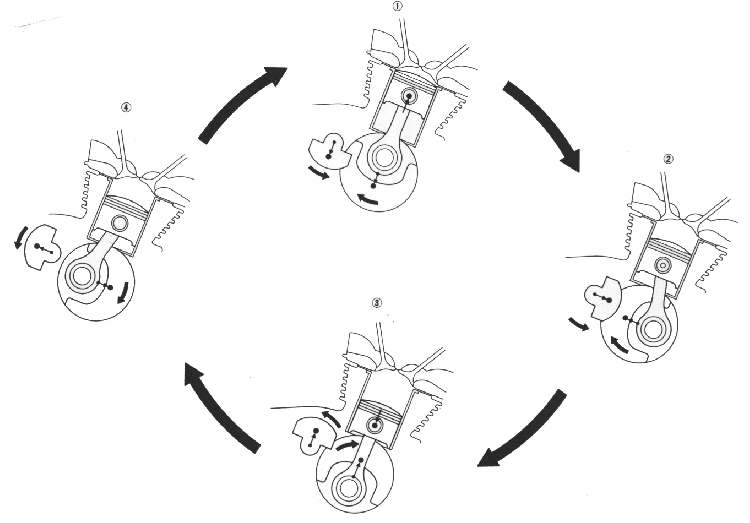

The single-cylinder counterbalancer at work:

That's how we get perfect primary balance. But there's also secondary balance to contend with.

The piston does not accelerate at the same rate in both directions or on every stroke. Acceleration is fastest after the spark plug fires and the fuel ignites, forcing the piston to descend. And in a four stroke engine, only the combustion stroke produces energy. The remaining three

consume energy, so the piston progressively slows until the next ignition occurs.

Since acceleration is less, so is momentum. That means there is a secondary imbalance caused by the act of breaking the fuel, an imbalance that the first counterbalancer is powerless to affect.

Fine, the secondary imbalance is merely another example of inertia and we can counterbalance that as well. The hitch is that this is a four-stroke engine and ignition only occurs on alternating revolutions. Which means the second counterbalancer also is to be gear-driven but will only turn at one-half the speed of the crank. That way the counterbalancer is at maximum acceleration only when the cylinder fires, and that's how we correct a secondary imbalance.

This explains why almost all single-cylinder 4-stroke engines are of very small displacement. The imbalances grow worse as the displacement increases because the sources of the vibrations -- the mass of the piston and the magnitude of the power pulse -- both are increasing as well. By the time the engine has significant displacement, you could just as easily have used the dynamics of additional, smaller (power-producing) cylinders instead of multiple (power-robbing) counterbalancers to reduce the shaking.

Some designs inherently possess better balance than others. The 1-cylinder, obviously, has a horrible primary

and secondary imbalance problem. Left to its own devices, it would like nothing better than to shake itself to pieces. The boxer-twin as in some BMW motorcycles has perfect primary balance but pretty miserable secondary. The inline-4 is similar, which is why your crotch rocket motorcycle needs a counterbalancer to quell the

buzzzzzzing.

But some designs are inherently perfect on both counts. The inline-six is the simplest design with perfect primary

and secondary balance. Others commonly seen are the "boxer" flat six (

a la the Porsche 911), the 90° V-8 and the V-12.

I find the V-12 particularly interesting because it is the fusion of two straight-sixes, which already have perfect primary and secondary balance. That perfect balance persists regardless of the included bank angle. It can be anywhere from 0° (making it a straight-12) to 180° and balance is unaffected. Because of a quirk in the mathematics in the delivery of torque, V-12s are smoothest (even smoother than the parent sixes) with included angles of 45°, 60°, 120°, or 180°.

One of my favorite automotive quirkies is the engine of the Ferrari 512 Berlinetta Boxer (built 1973-1984). It had a 5-liter, 180° V-12. Curiously it was not a "boxer" motor as it's name would have you believe (also sometimes referred to as a flat-12), it was a genuine Vee engine with a 180° included angle. So why did they call it a "Boxer"? I'm afraid you'll have to put that question to

Il Commendatore next time you see him.

But back to the V-10. It is the victim of the fact that every circle has 360° and each cycle of a four-stroke engine lasts 180 of them. It fires only once every 720°. As a consequence, the smoothest automotive engines tend to be the ones with a crank angle that is a factor of 180, usually 90 or 180°. There simply is no way to have ten pistons travel in a circle at regular intervals which also will permit a firing order that produces opposing (vibration-canceling) power pulses. There are some crank configurations (and firing orders) that favour primary balance. Others favour secondary balance. They even use clever split journals which allow the pistons sharing a single journal to be splayed by 18° (720° ÷ 10 cylinders = 72° per, and 72°+18° = 90°, a magic journal angle) but there simply is no one configuration that will make a V-10 run smoothly without a host of counterbalancers. It's not the development, it's the mathematics.

. Wonder why more manufacturers dont try and perfect the concept.

. Wonder why more manufacturers dont try and perfect the concept.

and stretch the bank angle of that V to 180° so that the pistons are horizontally opposed, like those in the boxer on the left, and "spin the motor," you'll see the pistons moving left or right in unison. Not only do they

and stretch the bank angle of that V to 180° so that the pistons are horizontally opposed, like those in the boxer on the left, and "spin the motor," you'll see the pistons moving left or right in unison. Not only do they